It was a historic moment for the American republic when earlier this month, a few cities of America elected mayors from the minority communities. These most talked about victories have suddenly brought back to light the works and speeches of Jawaharlal Nehru, considered to have vanquished after the demise of the NAM (Non-Alignment Movement). It is this “phoenix moment” for Nehru that we need to talk about. If seen against the backdrop of Trump’s anti-minority rants and campaigns, the victories secured by the mayoral candidates in New York, Virginia and Cincinnati are big ones for the secular-liberal forces.

As for those victorious candidates much talked about, let us look at their profiles before proceeding to make our point. Ghazala Hashmi became the first Indian-American as well as the first Muslim Lieutenant Governor of Virginia by defeating the Republican John Reid. She is the daughter of an AMU (Aligarh Muslim University) alumnus, Zia Hashmi. Aftab Karma Pureval, the son of a Punjabi father and a Tibetan mother, has been elected for the second time as Cincinnati mayor, defeating the half brother of US Vice-president, JD Vance. However, the talk of the town in the media was Zohran Mamdani, the 34 year old Indian-origin candidate, who won the elections to the mayor of New York. He was born in Uganda to the Columbia University academician, Mahmood Mamdani and filmmaker Mira Nair, moving to the US at the age of 7. In his winning address, he invoked Jawaharlal Nehru’s “Tryst With Destiny” speech.

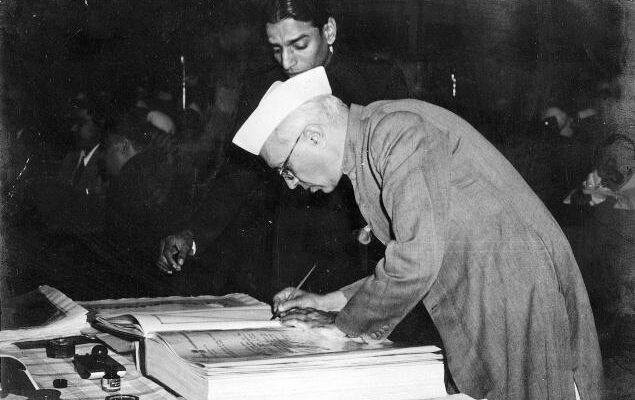

The speech marked Jawaharlal Nehru’s “phoenix moment”, his rise from the ashes after efforts had been incessantly made to erase his name and belittle his legacy in the last few years. It also proved that Nehru’s views on minorities remain relevant and it is the “Nehru way” that shall serve our purpose on minority rights discourse. Let us look at Nehru’s views on minorities and all that he did for the minorities.

Nehru’s Views on Minorities

Though accused by many scholars of having an inconsistent policy towards the minorities in general and the Muslims in particular, we shall see this was not the case. Nehru had a consistent approach towards the minority question and worked incessantly to solve this problem. On 4th January 1934, Nehru wrote about the formation of a constituent assembly for the solution of the many problems encountered by the nation at that time. He shared his views about a situation where if the Muslim members of the constituent assembly would be adhering to certain communal demands, then he would try to get them accepted. The reason for this was because “much as I (Nehru) dislike communalism, I realise that it does not disappear by separation but by a removal of the feelings of fear or by a diversion of interests. We should therefore remove this fear complex and make the Muslim masses realise that they can have any protection that they really desire. I feel that this realization will go a long way in toning down the feeling of communalism.” (Jawaharlal Nehru, Recent Essays and Writings, 1934, p.72)

Nehru was of the opinion that groups of upper class people mostly package their own class interests in the wrapper of communal demands of religious minorities or majorities. He wrote, “I am convinced that the real remedy lies in a diversion of interest from the myths that have been fostered and have grown up round the communal question to the realities of today”(Recent Essays and Writings, 1934, p.72). This diagnosis strikes the reader as poignant, particularly keeping in mind that works exploring this aspect by Anil Seal (1968), Peter Hardy (1972), Francis Robinson (1974) and David Lelyveld (1978) who vividly explored this aspect were still a thing of the future.

How Nehru Walked His Talk: Efforts at Making The Minorities Feel Belonging

The reason most academicians feel that Nehru had an inconsistent approach to the minorities is because they treat his speeches and deeds before independence in isolation from his speeches and deeds after independence. Therefore, we must start our analysis of Nehru’s works for the minorities from the Muslim Mass Contact Campaign of the Congress (1937-38). Nehru was of the opinion that “we have too long thought in terms of pacts and compromises with communal leaders, and neglected the people behind them.” He also announced that it was high time now to cast aside the older tactics of pacts and agreements with a reactionary Muslim leadership and instead reach out to the masses directly (Selected Works of Jawaharlal Nehru, Vol. 8, New Delhi 1975, p.128). While all the other historians have focused on the Muslim Mass Contact Campaign (MMCP) as largely a post- election phenomenon, Visalakshi Menon states that no assessment of the pre-office acceptance phase would be complete without taking into consideration the MMCC. (Visalakshi Menon, From Movement To Government, Sage Publications, 2003, p.72)

It was unfortunate that this campaign, a brainchild of Nehru, was abruptly called off and never again thought about, but it definitely suggested the sincerity of efforts by Nehru for the minorities. The best analysis on the theme is provided by Mushirul Hasan in his essay included in the edited volume India’s Partition: Process, Strategy and Mobilization (1993).

We shall now move to his works as the Prime Minister of India to establish a continuous link in his minority rights discourse. In the speech made on 19th August 1947, Nehru harped upon the fact that all citizens were to be treated equally. He stated that, “so far as the Government of India is concerned, it will deal with any communal outbreak with the greatest firmness. It will treat every Indian on an equal basis and try to secure for him all the rights which he shares with others” (Jawaharlal Nehru’s Speeches, vol.1, 1946-1949, p.66).

When the working of the constituent assembly (first meeting on 9th December 1946) had picked up pace, the sincerity of Nehru regarding minority rights became even clearer. ) His brand of inclusive nationalism is showcased

by the formation of a sub-committee on minority rights under the Advisory Committee on Fundamental Rights on 24th January 1947. The formation of this committee under the leadership of Sardar Patel meant that the lawmakers saw minority rights and fundamental rights as allied matters (Joya Chatterjee, Shadows At Noon, pp.88-89). The sincerity towards the first approach, that of allaying the fears of minorities can be gauged from the fact that by mid- July, the sub-committee had moved from the negative rights of the minorities as groups to the state’s positive obligations towards the minorities (Granville Austin, The Indian Constitution: Cornerstone Of A Nation, p.186 ). We shall also spare a word or two about the uncertain approach of Dr. Ambedkar on the issue. Pratinav Anil has shown us that while initially Ambedkar adopted the Hindu nationalist trope to address the minority (Muslim) issue, he later took a diplomatic position in ascribing a prescriptive role to the Instruction of 1935 which called for the state to attend to the rights of the minorities. His position was a vacillatory one when he stated that “strong and ‘stable governments’, perforce, demand artificial electoral majorities. He went on to paint a picture of anarchy under proportional representation: governments ‘would fall to pieces” (Pratinav Anil, Another India, p.93).

Nehru after his two day visit to the affected areas in Punjab, wrote to Gandhi on 21st August. He congratulated Gandhi for his efforts in Calcutta in reviving normalcy and at the same time urging him to apply his healing touch in Punjab as well which required it the most at that time (Pyarelal, Gandhi’s Last Phase, Vol.2, p.383). On his return from Calcutta on 9th September 1947, Mahatma Gandhi got the news of refugees from Pakistan attacking Kingsway Camp’s Hospital as a large number of Muslims were admitted there. He immediately ordered Sushila Nayar to proceed there and inform Sardar Patel and Nehru about her whereabouts. When Nehru reached the Kingsway Camp’s Hospital, he saw the refugees taking away valuables and immediately jumped out of the car and held a young fellow by his collar. Chiding away the crowd for such a dastardly act on their(refugees’)part, Nehru said – “have these Muslims done you any harm? If not then you must not injure them. We must be just. If justice requires it and it is necessary, we can go to war with Pakistan and you can enlist. But this kind of thing is degrading and cowardly”(Pyarelal, Gandhi’s Last Phase, Vol.2, p.435).

Nehru alongside Liaqat Ali tried to set up a joint Military Evacuation Organization but when it did not seem possible decided to send forces one country to the other to rescue people and assuage their fears (Joya Chatterjee, Shadows At Noon, p.90). The signing of the Nehru-Liaqat pact (1950) and other such efforts of cross-border cooperation largely at Nehru’s instance have been adeptly captured by Pallavi Raghavan in her book Animosity At Bay (2019).

Writing to the chief ministers in his letter dated 15th October 1947, he exhorts them to ensure the safety and well-being of the minorities at all costs. He also rubbished the talks of “Muslim appeasement” by the Congress that had been doing the rounds at that time (G. Parthasarthi ed. Letters To The Chief Ministers 1947-1964, Vol.1, OUP, 1985, p.2). Knowing fully well that the communal passions hadn’t died out by then, the pragmatist in Nehru appealed to do so for a bright international image of India, if not anything else. When Gandhi was shot dead on 30th January 1948, there was a rumour for sometime that this was the deed of a Muslim (Dominique Lapierre and Larry Collins, Freedom At Midnight, 1975, p.554). The first thing that Nehru did was, he clarified over the radio that the assassin was a Hindu, so that there were no anti-Muslim riots within the country. He banned the RSS and the next step for the protection of minorities by Nehru was banning publication of a number of English, Hindi and Urdu Urdu daily newspapers (9th February 1948) which were reporting quite irresponsibly (G. Parthasarthi ed. Letters To The Chief Ministers 1947-1964, Vol.1, OUP, 1985, p.60). He knew that any slander at this point from either side, with Gandhi gone, would result in a spate of violence. This strife would eventually turn into a vicious cycle of violence against the minorities.

Knowing the vulnerable position of Muslims at that time, he preferred not to jolt them further. Therefore, even while amending only the Hindu family laws, he emphasized upon the need for a

change in Muslim personal laws as well but the reforms shall come from within (Reba Som, Jawaharlal Nehru and the Hindu Code Bill, 1994).

Nehru’s Special Efforts for AMU

AMU was a potent Muslim (emphasis Gautier’s) symbol through which Nehru and Azad wanted to reach out to the Muslim citizens. Gautier argues that in practice, Nehru’s government turned primarily towards institutions identified as Muslim representatives either because of their religious nature as in the Jamiat Ulama’s case or their former association with Muslim politics, as in the case of AMU (Laurence Gautier, Between Nation and ‘Community’, 2024, p.72). Azad had recognised AMU’s significance for Indian Muslims and therefore, Nehru thought of giving it special patronage not only in order to make the minorities (particularly Muslims) feel secure but also to prepare the minorities to be ready for the approach of diversion of interests when the time came. On his first visit to AMU since independence, Nehru stated that, “I wanted to meet all of you and to probe somewhat into your minds and to let you have a glimpse of my own mind. We have to understand one another, and if we cannot agree about everything, we must at least agree to differ and know where we agree and where we differ ” (Jawaharlal Nehru’s Speeches 1946-1949, p.336)

Gautier has stated that by terming all the members present as Muslims, Nehru singled them out as a separate community that needed to be rallied around to the national cause. However, this was not the case as Nehru was both clearing the air about the Muslim loyalty from the hearts of Non-Muslims as well as urging the community through the University to focus upon adjustment and accommodation (the title of one of Mushirul Hasan’s essays) within the Indian union. By the Universities Act(1951), Aligarh Muslim University was granted the status of a central university simultaneously with BHU. Through this Nehru and Azad wanted to portray that Hindus and Muslims had an equal right to belong to the Indian state. He even intervened to safeguard the Zaidi sisters against harsh punishment by the UP government that had arrested them in a protest. This finds mention not only in Gautier’s book (p.121) but also in Inquilab Ka Ek Din by Zahida Zaidi (1995, p.72).

Conclusion

N.B. Khare in his My Political Memoirs/Autobiography (1959) states how Nehru invited the wrath of his own colleagues and Hindu communal organisations for the measures he took for the minorities. Mushirul Hasan in his essay “Recalling Radical Days at Aligarh” (2003) states that, “people in the university discussed among themselves about Nehru being the saviour of the university after partition.” The same can be held true of the minorities throughout the country. So, it will not be a false proposition for the initial years after partition that, “if Muslims had a leader at all, it was Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru” (Badruddin Tyabji, The Self in Secularism, p. 126). Therefore, Nehru’s approach to the minority rights discourse might not be the “verzweifelten Ausweg” (a term used by Prof. Sajjad Ather and S.K. Singh in their book The Physics of Neutrino Interactions) but it is certainly worth giving a chance.

[The writer is a doctoral candidate at the Department of History, AMU]