Twenty-five years ago there died two important Indians, two exceptional human beings; one better known than the other, but both significant for what they professed and practiced all their lives. E.M.S Namboodiripad was instantly recognizable to millions of his countrymen; fewer Indians knew of the greatness of Bishop Paulose Mar Paulose, which is not right but understandable.

Marxists have come to power not always by the bullet; the ballot is not anathema to many amongst them. It is common knowledge that EMS headed the first freely elected Communist government anywhere in the world when the people of Kerala voted it to power in 1957. Its dismissal two years later had more to do with intrigues hatched in New Delhi than the alleged incompetence of the Trivandrum regime.

Winning popular mandate by peaceful means is one thing; being allowed to govern in peace quite another, as proved by the problems EMS had to face 66 years ago. Of course, all this is now history which may not be familiar or interesting to today’s young Indians, many of them involved as they are in attitudes and ambitions of a different order.

Adoor Gopalakrishnan’s film Kathapurushan (Man of the Story), which examines the life of a creative individual with a dissident temperament from childhood to adulthood during an extended politically turbulent period in Kerala (1937-80), evokes memories of, among other things, the time when EMS swept to power and his subsequent dismissal.

The Kerala experience of democracy being throttled unjustly has been repeated more than once in Latin America, only in a far more brutal fashion. Fifty years ago, in 1973, the Chilean people, disgusted with a long line of conservative and mediocre leaders who had exercised power more for their own benefit than for the common weal, elected a physician-turned-public figure Salvador Allende Gossens as the world’s first democratically elected Marxist head of state. But, as with EMS in Kerala, Allende was prevented from functioning in the manner he thought would be conducive to popular good.

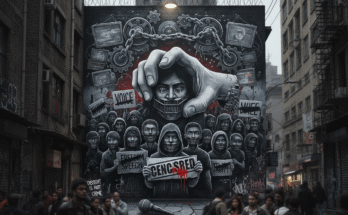

Socially-conscious people all over the world now know how Chile’s army chief, Augusto Pinochet Duarte, acting on orders from Washington and guided by the CIA, crushed Allende’s Popular Unity Government and imposed a military dictatorship that was to last for 17 years. Allende was shot 13 times after his refusal to resign; thousands of Allendistas in the student community, in the trade unions and among professionals, artists, intellectuals and the clergy were liquidated. To this day, no one knows what became of the remains of many of those principled young men and women, or how they spent the last hours of their lives – reminiscent of the tragic fate of their counterparts in Bengal, Bihar, Kerala and other parts of India at about the same time.

Pablo Neruda, Chile’s Nobel-winning poet and the lyrical conscience of his people, who was also killed by the generals, writes in his memoirs about Allende’s principles, his remarkable style of functioning, and his great humanity: “Allende was never a great orator. And as a statesman, he never took a step without consulting his advisers. He was the anti-dictator, the democrat of principles, even in the smallest of particulars….Allende was a collective leader; although not from the popular classes, he was a product of the struggle of those classes against the paralysis and corruption of their exploiters”.

The ‘exploiters’ Neruda mentions included most noticeably the copper multinationals, Anaconda, Kennecott and Cerro. One of the reasons why Allende was murdered and his experiments with truth prematurely ended was his decision to nationalize the principal wealth of Chile’s sub-soil – copper. An uncompromising democrat who lived by the book of eternal verities, he and countless of his comrades were sacrificed so that the juggernaut of foreign exploitation, actively assisted by local agents, could roll on unhindered.

More than one Latin American artist has brought to the screen images of the coup, its aftermath, or the tentative return of democracy to Chile (tentative because neither Pinochet nor any of his accomplices were punished for their crimes against humanity), but none with greater accuracy and feeling than Patricio Guzman, the Chilean documentarian best known for his celebrated The Battle of Chile. That three-part epic documentary showing the steady rise and induced fall of the Allende regime is rightly counted even after several decades of its making as one of the lasting riches of New Latin American Cinema, that remarkable body of work that brings to the fore the flawed destiny of a continent in ferment. Other Guzman journeys into the scarred soul of the Chilean people in the wake of the coup include Chile, Obstinate Memory, which movingly fuses the past in the shape of clippings from The Battle of Chile with the present as expressed in interviews with some of the survivors of the coup as also with young men and women whose impressions of the catastrophe are based largely on what they have been told by older people.

It is a remarkable coincidence that two dissimilar personalities, one an atheist and the other a man of God, who nonetheless shared many common ideals when it came to service to fellow-men, should have left the world within weeks of each other. On March 24, 1998 Bishop Paulose Mar Paulose (57) of the Chaldean Syrian Church of the East died in Chennai following heart surgery. (Namboodiripad was, of course, much older and, as such, was able to fight more numerous battles in support of the poor.)

In the second week of April, 1998, Zanussi, the Polish filmmaker, sought to enliven the dull proceedings of the third International Film Festival of Kerala (IFFK) in Trivandrum, when he claimed that “the Christian vision of the world is far more revolutionary than Communism”, and took other potshots at Marxists.

These two seemingly unrelated events – the death of the Bishop and the comments by the filmmaker – are not so distant from each other as they may appear to be. Whereas the once-reputed Zanussi who had subsequently been disappointing cinephiles by being less of a filmmaker and more of a born-again fundamentalist, wants to characterize the Marx-Christ debate as a battle between opposites and irreconcilables, Bishop Paulose struggled all his priestly life for the liberation of the poor and the oppressed in the belief that the matter is more in the nature of a competition between rivals and equals.

It is difficult to believe that Zanussi is unaware of a blessing called Liberation Theology; of the influence of Marxism on modern interpretations of the Bible. In many Christian (particularly Catholic) circles, liberation theology is an accepted feature of the language of love and service to humankind. Briefly, it is an idea that, given the severely imperfect conditions in society – especially in the vast neo-colonised underdeveloped world – methods of active intervention become necessary at times for the material and spiritual liberation of the poor and the powerless. It would not be incorrect to say that liberation theologians are activists in the non-classic Christian mould. In their espousal of a fierce love for their flock, combined with their belief in the efficacy of leading from the front as and when necessary, many a liberation theologian has lost his head, literally. The case of a Jesuit priest being beheaded in 1997 in south Bihar in what can only be said to be the outcome of taking one’s duties towards the poor too seriously, is still fresh in this writer’s mind. Obviously, far better placed are those churchmen ensconced in such havens of tranquility as high-profile business schools or such other educational institutions patronized by the genteel and the high-heeled.

For hundreds of years, priests, nuns and lay upholders of the Catholic Church allowed themselves to be dictated by the Vatican hierarchy – a white and wealthy set-up. There were stray cases of resistance which were sternly dealt with. But in the past half a century or so, increasing numbers of dissenters have refused to take things lying down, especially in the hills and jungles of south and central America. The ‘Western’ Church, as distinct from the Church of the ‘godforsaken’, has retaliated with punishments like excommunication and, in extreme cases, has even connived with military dictators and unprincipled politicians to teach a good lesson to the less than obedient. (The dictator Anastasio Samoza of Nicaragua immediately comes to mind, who had to bow out under pressure from the Marxist Sandinistas, aided by a section of the Catholic clergy in that small but strategic central American country.)

Bishop Paulose, whose untimely death is still mourned in both Church and Communist circles in Kerala and beyond, used to speak of a “new spirituality of combat” if any amount of justice was to be wrested for the poor; and of a “religionless Christianity”, first advocated by the German theologian, Dietrich Bonhoeffer who was sent to the gallows by the Nazis, along with his brother and brother-in-law. One wonders what conservative Papists would make of the ‘Red Bishop’s’ famous exhortation: “Even if an ideology does not have the blessings of the Church, if it strives for the welfare of the poor and the underprivileged, it is the duty of all true Christians to support and propagate that ideology.”

As chairman of the World Christian Students Federation, Bishop Paulose carried his unique understanding of the message of the Bible to far corners of the globe, but nowhere with a greater sense of urgency than the poorest and most exploited societies. At a time when our country, as indeed most countries, finds itself woefully short of role models – that is, people with courage, compassion and the capacity to think creatively when the chips are down – the absence of an extraordinary soul like the Christian yogi should be a matter of huge sadness to all Indians of goodwill and active interest in the furtherance of an eclectic and egalitarian society. A statesman like Bishop Paulose comes in a long while to show us by his deeds, the difference between the ideal and the commonplace.