The 75th Independence Day of India is practically the first for workers in the country without the official protection of crucial labour laws, like the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947, the Factories Act, 1948 among others. Some of these laws are as old as the country’s independence itself, and all of them, in principle, aimed to safeguard workers’ basic rights and the condition of their freedom. Over the course of 2019-20, these have now been replaced by four new Labour Codes: The Code on Wages, the Industrial Relations Code, the Code on Social Security and the Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions Code.

PUDR marks this occasion by releasing its report, ‘The Anti-Labour Codes’– on labour laws that, instead of protecting labour rights, actually take them away. The report offers an overview of the content of each of the four Codes with their implications on the rights of workers, while contextualizing them against the government’s pre-existing policy of ‘Ease of Doing Business’ and the de facto non-compliance with legal provisions even prior to their enactment.

Find the report here: https://pudr.org/anti-labour-codes

The report brings to light how several aspects of the Labour Codes have been practically in place for a few years even prior to their formal enactment, in pursuance of the government’s Business Reforms Action Plans. PUDR’s fact-finding investigations into labour issues in Delhi-NCR over the last six years or so, media and other reports reveal the growing problems of workers across sectors and industries. These include increasing precarity through long hours of work, job insecurity, contractualization, unjust wages, ‘compulsory’ overtime, as well as lack of safety and fatal workplace accidents. These were compounded on account of non-implementation of previous labour laws by the state’s regulatory and enforcement mechanisms – the Labour Department and the police. Many of the key provisions later enacted as part of the Labour Codes had already been put into place on the ground through executive writ- a practice which gained further impetus during the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the obvious distress workers were facing, central and state governments passed a series of executive orders through 2020-21 that fundamentally amended and sought to partially or completely suspend labour rights, citing the pandemic as cause. In the midst of these developments, three Labour Codes were passed in Parliament in September 2020 bypassing procedures for democratic debate and deliberation (one had already been pushed through in 2019).

The four Labour Codes, their content and implications, can only be understood in the light of the above and by seeing the way in which the Codes work together. PUDR’s report ‘The AntiLabour Codes’ shows how these separately and together, while promoting ease of business, effectively work against the interests of workers, and contribute to labour’s considerable prior precarity (see Table 2: Cumulative Impact of Labour Codes 2019-20 in report). The report highlights several concerns, with key issues excerpted below:

(1) Extensive discretionary powers to ‘appropriate governments’ to determine crucial aspects pertaining to labour – e.g., minimum wages, identifying eligible workers, determining safety standards, defining hazardous work etc. Such ‘flexibility’ can be fatal.

(2) Reduction in liability of owners/ management in case of safety violations, and availability of wide exemptions for a number of industries from complying with even important legal obligations towards labour.

(3) Dilution in enforcement mechanisms and employer liability, e.g. the position of Labour Inspector is renamed ‘Inspector-cum-Facilitator’, directed to facilitate business, and deprived of the post’s earlier quasi-judicial powers. Combined with absence of physical inspections, measures like online self-certification of compliance by owners etc., this implies employers guilty of violating workers’ labour rights will have impunity.

(4) Denial of access to Courts i.e., civil court jurisdiction barred for industrial disputes; replacement of Labour Courts by Tribunals with one administrative and one judicial member, increasing executive control.

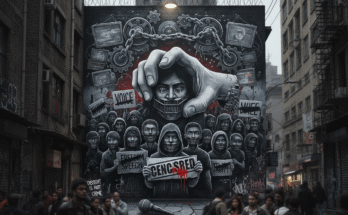

(5) Serious restrictions on the rights of workers to unionize, take collective action and seek legal redress against violations of their rights.

(6) Claims of allegedly extending protection to certain categories of workers such as social security for gig workers rings hollow as they suffer from the same vice of lack of enforcement mechanisms and dilution in employer liabilities. Most employers/ contractors evade liability by simply identifying gig workers as independent contractors and not as workers at all.

As such, the Labour Codes serve to formalize this existing reality of regulatory non-compliance by industries, and act as the final nail in the coffin of workers’ rights under law. By removing or undermining previously recognized rights, rendering judicial and other institutions inaccessible to workers, and severely restricting rights to unionize, workers are deprived of whatever formal legal avenues existed to challenge violations through collective action. If ‘Ease of Business’ can only be achieved at the cost of labour, and ‘flexibility’ secured only by surrendering workers’ basic and democratic rights, then the state’s pursuit of ‘Ease of Business,’ culminating in the Labour Codes, should cause grave unease to all citizens.

– Radhika Chitkara, Vikas Kumar

Secretaries, People’s Union for Democratic Rights (www.pudr.org)